BLOG: APPLIED RESEARCH OF EMMANUEL GOSPEL CENTER

Feet Fitted with the Gospel of Peace

When one part of the body suffers, every part suffers with it. What does it look like for us to show up with hope alongside immigrants in a time of fear and disconnection?

(Clockwise from top left: Welcomia, Denis Tangney Jr, captain_galaxy, YT, all via Getty Images)

Feet Fitted with the Gospel of Peace

A prayer walk, a prophetic dream, and a call to stand with our immigrant brothers and sisters

by Sarah Blumenshine, Director, Intercultural Ministries

One of the beauties of my work is connecting deeply with immigrant communities in and around Boston. This summer I’ve been attending regular morning prayer calls led by the Agencia ALPHA team over Zoom. On a recent call, Pastor Sergio Perez of Harvest Ministries in Weymouth invited us to join an upcoming prayer walk in the city of Lynn. About a dozen of us showed up the following Saturday. Pastors joined hands with families and seniors. We were all there for one purpose: to pray protection and blessing over the city.

Before we broke into groups and began our walk, Pastor Sergio shared a dream he’d had more than 15 years ago. This dream took place on a particular street corner in Lynn. Exactly what is happening now across the country was playing out in his dream. Officers were rounding up immigrants and loading them into a bus. Families were terrified, trying to get away. In his dream, Pastor Sergio approached the officers and told them that they needed to take care. He asserted that immigrants have dignity and humanity and deserve decency. The officers seemed to pause and were somewhat affected, and then Pastor Sergio woke up. The dream felt so real that it stuck with him.

When we paired off and picked a direction to walk, Pastor Sergio headed in the direction of the street corner he’d seen in his dream. I teamed up with Patricia Sobalvarro, Executive Director of Agencia ALPHA, and Pastora Ramonita Mulero of Iglesia Hispana de la Comunidad. Together we began walking toward a nearby Market Basket grocery store, where many immigrants find employment. We prayed through Ephesians 6:10-18 about putting on the armor of God, asking for truth, for faith, for the protection that comes not from our own efforts but from the astonishing goodness of God.

Something struck me that I’d not seen before. I’ve always associated this passage with spiritual defense. But this time, the instruction to stand firm “with your feet fitted with the readiness that comes from the gospel of peace,” landed in a fresh way. Even in battle against spiritual darkness, we are told to wear shoes that can bear us quickly elsewhere to share the good news of peace! Such hope, even certainty.

As we walked, we passed immigrant-owned shops, houses, and apartments. We recalled the passage in Exodus where God told the Israelites to paint the blood of a lamb over their doorframes as a sign for the angel of death to pass, thereby sparing their firstborn sons. We covered homes and businesses and sidewalks and churches with pleas for physical protection, praying that violence would pass them by.

Patricia shared a reflection on the story of the Israelites finally expelled from Egypt, only to have Pharaoh change his mind. He sent chariots and soldiers to pursue and enslave them again. Meanwhile, the Israelites were approaching the Red Sea with nowhere to go. Patricia remarked that she has often wondered how she would have felt had she experienced that moment. Every step closer to an impassable body of water would have seemed like impending death. When things seemed most desperate, God made a preposterous way through the sea. We prayed for these kinds of miracles, admitting we could see no way through, but God surely could.

“Put on the full armor of God, so that when the day of evil comes, you may be able to stand your ground, and after you have done everything, to stand. Stand firm then, with the belt of truth buckled around your waist, with the breastplate of righteousness in place, and with your feet fitted with the readiness that comes from the gospel of peace.”

When we returned to the church parking lot, each group offered a few words about their experience. Another pastor who was present started sharing, first to the whole group, and then he turned and spoke specifically to me. Because I am still learning Spanish, I only understood a fraction of his testimony, but I know our hearts saw each other. He spoke with deep passion, such that he started weeping.

When the pastor finished speaking, Pastor Sergio asked how much I had understood. Seeing my uncertainty, he kindly translated the pastor’s words. He explained that my presence—and what I represent as a U.S.-born citizen—carried a certain weight. He related how many immigrants feel isolated and unseen by others. They feel invisible to their Christian brothers and sisters in this country. The fact that someone from that context would see their suffering and journey with them was overwhelming to the pastor who shared. Pastor Sergio compared it to the story of the British politician William Wilberforce, who, despite his privilege and comforts, identified with the plight of enslaved people and became an advocate for the ending of slavery.

I was stunned. I hadn’t done anything extraordinary; I had simply shown up to pray, side by side with my sisters and brothers. Truthfully, it felt like the bare minimum my spiritual siblings should expect. Jesus told us to love one another as we love ourselves. Geography, international boundaries, human laws—these are all important. But not one of them stops us from being part of the same family, the same body.

“The parts of the body will not take sides,” Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 12:25-26. “All of them will take care of one another. If one part suffers, every part suffers with it. If one part is honored, every part shares in its joy.”

Lately, I’ve had an image in my head of the Church in the United States as a human body suffering from neuropathy. Our nervous system, the network that carries sensation and information and generates feedback, is damaged. Our ability to perceive one another is scrambled. I imagine someone standing next to a hot stove, hand on the burner, completely unaware that skin and tissue are melting until they smell the burning—but by then, the damage is done.

Friends, parts of the body of Christ are on fire. I do not exaggerate. I am one nerve that transmits impulse and effect. I bear witness to that agony. We are poor in relationships that cross cultural lines. Our relational distance allows us to dehumanize the “other.” We forget that we’re kin. We fail to see that our thriving is enmeshed.

“This body of Christ desperately needs healing. It is at war with itself. Healing starts within each one of us. What kind of fruit am I nurturing with the substance of my soul? In the communities I am part of, are we together seeking the flourishing of all people?”

The current level of chaos in the federal government is a smoke screen that further obscures our view. Some of us have swallowed the lie that law and punishment are righteous, but compassion is only for those who deserve it. This falsehood is antithetical to the life and ministry of Jesus.

Laws have their purpose in a well-functioning society, to be sure. If we are fueled by love and joy, filled with the fruit of the Spirit, we will work with others to correct immoral laws and apply them with fairness.

In contrast, today the fruit of our policies and power is on grotesque display. Every human being suffering in a detention camp with no legal recourse, every person deported to a country that is not their own, each careless arrest, every child who cries for their missing parents—these we cannot brush off as collateral damage. They are the fruit of fear, resentment, self-righteousness, and a will to dominate. They are what happens when laws are weaponized as instruments of oppression.

This body of Christ desperately needs healing. It is at war with itself. Healing starts within each one of us. What kind of fruit am I nurturing with the substance of my soul? In the communities I am part of, are we together seeking the flourishing of all people?

We remember our kinship by listening to one another. We dedicate the time and attention required to understand each other. We choose to take simple but significant steps, such as joining our hearts in prayer. These habits are transformative, and they give rise to new points of connection that slowly help us repair what has been broken.

As we commit ourselves to this way of life, everyone doing their part, honoring one another’s pain and celebrating each other’s joys, we begin to experience the body as God intended. God’s design is for the Church to be an agent of hope, healing, and reconciliation both within and without. May it be so.

What happens when church buildings close?

Churches faced with aging buildings, lack of parking, and aging, dispersed membership may find selling their buildings necessary—or even advantageous. What happens to the buildings when they do?

Trends and status of Christian institutional property ownership in the City of Boston

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher

Boston is home to about 575 Christian churches. While many of these rent space from other churches, organizations, or private owners, a significant number of congregations own and meet in traditional church buildings, former commercial properties, or converted residential buildings.

Currently, churches and their denominations own about 320 properties in Boston, including 256 buildings primarily used for worship, ministry, and service.

In recent decades, some church-owned buildings have been sold to other congregations, developers, and private business owners. As a result, about 45 buildings formerly owned by churches or religious organizations have been lost to the Christian community as well as the communities and neighborhoods these churches once served and called home.

These churches not only contributed to the spiritual well-being of their neighborhoods but also played an important role in sustaining the social fabric of their communities. Many provided a variety of social services and enriched civic life. Memories of important life events were tied to these sacred spaces.

As a result, the loss of these congregations and sacred spaces has had a deeper impact than is often realized.

In a constantly changing city and culture, there are many reasons why congregations decline, and church buildings are sold. To stay vital to the life of the community, churches require spiritual renewal and the ability to adapt to younger generations. Shifting demographics also can affect congregations, particularly when their members move to different areas farther from the church building.

In the Boston area, this movement of people is influenced by ever-rising housing costs and, in some neighborhoods, gentrification: the process of higher-earning and more educated residents moving into historically marginalized neighborhoods. While gentrification brings increased financial investment and renovation to a neighborhood, it often also leads to a rise in housing costs, which results in the displacement of long-time residents. This dynamic disrupts congregations, as church members may be displaced or move elsewhere. Churches faced with aging buildings, lack of parking, and aging, dispersed membership may find selling their buildings necessary—or even advantageous. Sometimes, congregations that were renting space are no longer able to afford the cost.

What happened to these buildings?

Congregations, which own and meet in residential houses, often adapted the first-floor space for worship. In several cases, when sold, the new owner has changed the occupancy, converting the space into a residence and adding an additional unit.

Iglesia de Dios Pentecostal at 68 Day St. in Jamaica Plain used the first floor for church services, but after the building was sold, the first floor was changed into a residential unit.

The Greater Community Baptist Church at 27 Howland St. in Roxbury used to meet in a converted house with a brick addition on the front. When this property was sold, the new owner removed the addition and converted the building to a two-family house.

Iglesia de Dios de la Profecia owned a tax-exempt converted house at 20 Moreland St. in Roxbury, which was sold and converted into a private two-family residence.

On Melville Avenue in Dorchester, the Salvation Army used a large house and 35,000-square-foot lot as a ministry center and church called Jubilee Christian Fellowship. When sold in 2022, the property was turned into a two-family luxury residential building.

While several houses used as church buildings have been sold, congregations such as the Church of God and Saints of Christ on Crawford Street and Spirit and Life Bible Church on Columbia Road continue to meet in converted houses.

In the past, numerous churches met in commercial or storefront properties, even in neighborhoods like the city's South End. Some storefront churches rented space, while others purchased the buildings when prices were relatively low. As rental prices rose and neighborhoods gentrified, several churches renting storefronts had to move out or close.

One rental storefront church space became a dental office, and another became a restaurant. Several church spaces have become laundromats. For example, the Full Life Gospel Center in Codman Square decided to sell its storefront property and buy another Dorchester church building whose Haitian congregation had moved to a former synagogue in Randolph. The former Full Life Gospel Center property on Washington Street was then renovated into a laundromat.

“Over the last 50 years in Boston, as the city has changed and property has become much more expensive, many former storefront churches have disappeared.”

Although churches, which own commercial-type space, generally have not needed to move, some have chosen to sell and relocate or buy other buildings. Grace Church of All Nations in Dorchester chose to sell its storefront property to a CVS Pharmacy and purchased a former Christian Science Church in Roxbury. Over the last 50 years in Boston, as the city has changed and property has become increasingly expensive, many former storefront churches have disappeared.

From the 1950s to 1970s, as neighborhood churches in Boston declined and congregations were leaving the city, many church buildings and synagogues were sold or passed on to new Black, Haitian, or Hispanic congregations. In recent years, some church buildings have been sold to other congregations, while many others have been lost to the religious community altogether.

Some churches with valuable properties may have concluded their assets could be better spent on more extensive, less expensive, and more modern facilities in other areas, closer to where their congregants live. Those congregants who used to live in Lower Roxbury, Roxbury, or Dorchester may now live outside the city because of escalating housing costs in Boston. Although some churches that have sold city buildings have rented temporarily, most have purchased other buildings.

The 45 church buildings cited earlier represent over 30 congregations that have closed permanently. Others have either moved elsewhere in the city—such as Grace Church of All Nations, New Hope Baptist Church, Full Life Gospel Center, Mount Calvary Baptist Church, Church of God of Prophecy, Boston Chinese Evangelical Church—or moved out of the city—such as Trinity Latvian, Christ the Rock Metro, Concord Baptist Church, and Ebenezer Baptist. Some congregations, such as Holy Mount Zion Church, New Fellowship Baptist/Spirit and Truth, and Mount Calvary Holy Church, are left in limbo due to fires, structural deterioration, or financial constraints.

Although some churches have relocated outside the city of Boston, the overall number is still relatively small compared to the total number of churches currently in the city. As lower- and middle-income Boston residents, as well as new immigrants, settle in communities farther from downtown, new churches are also starting up in these communities. At the same time, inner-city churches are losing members who no longer commute back to their former congregations.

When traditional church properties are sold to non-church buyers, they are mostly converted into market-rate residential units, such as condos or apartments. However, there are notable exceptions to this: St. James African Orthodox Church in Roxbury, Hill Memorial Baptist Church in Allston-Brighton, and Boston Chinese Evangelical Church in Chinatown.

St. James African Orthodox was rescued from demolition and private development through neighborhood activism and the help of Historic Boston, Inc., which purchased the building, made repairs, and eventually resold it to a community organization, the Roxbury Action Program. (In the process, Historic Boston, Inc. tried to interest other churches and community organizations in developing the building cooperatively; however, no churches could take on the project.)

Hill Memorial Baptist worked with a neighborhood development organization and the City of Boston to see their church sale result in plans for affordable senior housing, with the church building preserved to serve as a social center for the new residents. The church, its denomination, and the Allston Brighton Community Development Corporation went through a five-year partnership and planning process to achieve positive outcomes for the community and church.

Boston Chinese Evangelical is another unique example of a traditional church-building sale. Over the years, church leaders were in dialogue with the City of Boston and the Boston Public Schools about their church building and property in Chinatown, which was in a strategic location next to the Quincy Elementary School. After the congregation purchased a large, nearby building at 120 Shawmut Ave., it sold its church building to the city. The church building was demolished, and the new Josiah Quincy Upper School was built on the site.

While the St. James African Orthodox and Hill Memorial Baptist congregations closed, the Boston Chinese Evangelical congregation continues to use a diverse portfolio of property that includes rented worship space at the Josiah Quincy Elementary School, its multi-purpose building at 120 Shawmut Ave., and a Newton, Massachusetts, satellite church building.

Preserving and sustaining church congregations and their properties is critical for the health of Boston’s neighborhoods. Churches’ physical and spiritual presence contributes to their communities on many levels.

Congregations that want to stay in their current neighborhoods can seek ways to serve others and sustain themselves by renting space to community groups or other congregations. Churches looking to close or relocate and sell can plan and consider positive outcomes for their building by selling to another church or community-serving organization. They can also work to see community development efforts, such as community centers or affordable housing units, built within the church or on its site.

Why isn’t my church talking about race?

Many white Christians in evangelical churches feel isolated in their desire to discuss race, often encountering silence or pushback from their communities. Engaging with racial issues from a biblical perspective is essential for fostering unity and effectively following Jesus in a diverse world.

Photo credit: Shaun Menary via Lightstock

Many white Christians in evangelical churches feel alone in their desire to talk about race

by Megan Lietz, Founding Director, Race & Christian Community Initiative

It came from the look in the pastor’s eyes, the awkward pauses in the conversation, the tone that, while appropriate to the passing ear, couldn’t help but feel patronizing. Here I was again, having my faith held suspect because I believe Jesus calls Christians to engage in issues related to race.

At that moment, I knew I had about 30 seconds to establish I was “one of them.” To assert my faith and prove I really am a Bible-believing Christian. There was no time to share that I was born and raised in white evangelicalism, with my teenage years defined by youth conferences and summer missions trips, WWJD bracelets and promise rings. There was no time to mention I believe the Bible is the Word of God and that I learned to study it at evangelical colleges and seminaries. No time to talk about how much my faith means to me, what it has brought me through, or my deep love for Jesus.

It was as if none of that mattered. Certainly, none of it was seen. All it took was the word “race,” and I was written off as a “liberal.”

It was all right. It was a brief interaction with a pastor I had never met before and would probably never see again. Yet it represented a painful reality I often hear about from white brothers and sisters in theologically conservative churches.

“It was as if none of that mattered. Certainly, none of it was seen. All it took was the word ‘race,’ and I was written off as a ‘liberal.’”

One brother shared he feels the discipleship he received did not prepare him to engage our multiracial reality. Another sister said she had to leave her beloved church community after many years because she no longer feels at home in an environment that regards race as a side issue.

The challenges white folks encounter when exploring issues related to race don’t compare to the pain and oppression experienced by people of color. Yet, it is essential for white people to learn how to navigate the obstacles we encounter so we can be better positioned to experience and contribute to racial healing.

Many white brothers and sisters who participate in the Race & Christian Community Initiative (RCCI) often express how refreshing it is to be able to talk about race in the context of Christian community. Sadly, even though these issues are coming up in conversations around the water cooler and blowing up their news feeds, they’re not able to discuss race in their congregations. It’s not mentioned from the pulpit, explored in Bible studies, and certainly not a topic for casual conversation.

Even if it is explored at those lamentable moments when racial violence captures our collective attention, the conversation’s life cycle often mirrors that of the news cycle: a one-off here, a one-off there — reactive events choked out by donor pushback and competing priorities.

When churches don’t talk about race, white folks who care about the issue can often feel isolated at best. Well-meaning comments about “slippery slopes” and how “race is a distraction to the gospel” can make us feel frustrated, suspect, or unwelcome. It can even lead to a crisis of faith as we start to believe the lie that the Living Word does not speak into the realities of racial injustice.

Engaging issues related to race from a biblical perspective does not cause us to lose our faith. It helps us follow Jesus more faithfully.

White evangelicals’ disengagement from race has little to do with Scripture. On the contrary, the Scriptures we highly esteem speak abundantly into the issues of unity, diversity, ethnicity, culture, power, oppression, healing, and justice. Our disengagement can be explained — not by God’s heart — but by the result of social and historical realities.

For example, as members of the dominant culture in the U.S., we often don’t have to think about race. Our social location can make us oblivious to the realities of racism.

“The Scriptures we highly esteem speak abundantly into the issues of unity, diversity, ethnicity, culture, power, oppression, healing, and justice.”

Closely related to this, white folks tend not to explore race in our theology. This dynamic is especially problematic when most Christian educational institutions center Euro-American theology as normative and comprehensive. It has left many Christians less aware of God's heart for justice and how the interconnected body has experienced the God of justice in their lives.

The fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the 1920s and ’30s led theologically conservative Christians to largely disengage from social issues so they might distinguish themselves from more theologically liberal expressions of the faith. The impact of valuing orthodoxy over faithfully living into Jesus’ heart for justice continues today.

Because of realities like these, white evangelicals lack the experience, theological frameworks, thought leadership, and examples from within our traditions to build shalom across racial lines. While this can make starting the conversation even more intimidating, we cannot afford to stay silent. When we don’t address issues of race, we do damage to the kingdom of God.

Whether white evangelicals acknowledge the problem or not, we are complicit in the ways racism harms our brothers and sisters of color, diminishes ourselves, and dishonors the image of God. When white congregations don't talk about race, there are significant consequences:

Disunity: Christian communities remain segregated. While being in a racially homogenous congregation is not bad within itself, it becomes a problem if white congregations are homogenous because people of color do not feel welcome, included, or cared for. This can often be the case if congregations are not talking about race, culture, or power dynamics that many people of color experience as a regular part of life.

Church hurt: We lack the discipleship needed to build shalom across racial lines, allowing the perpetuation of racial brokenness in and through Christian communities.

Diminished witness: The harm done and the deeply-seated division in the Church diminish Christian witness. When we know the Great Physician but aren’t working toward racial healing, we miss out on opportunities to demonstrate God’s power and presence.

Waning influence: When the Church isn’t even speaking into a sorely felt need in our society, we shouldn’t be surprised when people stop listening. Instead of proclaiming that Jesus is good news in the midst of racial brokenness, too many white Christians have remained silent and are allowing secular organizations to lead the way.

“We cannot afford to stay silent. When we don’t address issues of race, we do damage to the kingdom of God.”

It doesn’t have to be this way. The Bible offers principles, parallels, and language white Christians can use to talk about race. We can also learn from the traditions of Black, Indigenous and people of color, who have rich legacies of addressing racism. There are also numerous resources by evangelical publishers and denominations on how our faith connects to race.

There are paths ahead. But too often, fear, competing priorities, and well-trodden pathways get in the way.

RCCI creates spaces where white Christians can talk about race. Be it learning communities for white evangelicals, conversations over coffee, or opportunities to reflect on and learn from serving across racial lines, we desire to create a place where white folks can learn and grow in Christian community. We also come alongside predominantly white congregations, meet them where they are, and help them take the next step in exploring issues related to race from a biblical perspective.

The richness of RCCI comes not because we get it all right, but because we create spaces for people to have conversations the Lord is already stirring within them. With love and grace, we create opportunities for the Lord to continue the work he desires to do. And as we invite him in, we see healing, we see hope, we see perspective transformation. What excites us most is seeing people move from talk to action, bearing witness to the person and power of Jesus by continuing his redemptive work across racial lines.

Will you join us in talking about race? Will you learn with us as we explore the conversation? We don’t always say the right thing, but we long to know the Lord more fully, serve him more faithfully, and usher in his kingdom by how we engage across racial lines.

College Ministries and Churches Serving University Students

This guide includes Boston-area Christian campus ministries and a sample of churches serving college students.

Skyler via Lightstock

College Ministries and Churches Serving University Students in Boston

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher

With its 150,000 students and 35 colleges and universities, Boston has long been known as one of the leading college towns in America. The greater Boston area has about 50 colleges and universities and over 250,000 students. Known as the Athens of America, Boston also hosts many thousands of international students, scholars, and researchers.

Here is a selective guide to some Boston-area Christian campus ministries and a sample of churches serving college students.

If you are a prospective student, parent, youth worker, or advisor, this information can help you find a Christian group or staff worker. If you believe God is calling you into campus ministry, Boston is a strategic area with many opportunities for ministry. If you have a concern to pray for Boston-area campuses, students, and ministries, this guide provides an overview and some information to start with. Current students with questions about God or the Christian faith can use this guide to find fellow students or campus workers to talk to or meet with.

General Campus Ministries

InterVarsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF)

"The purpose of InterVarsity Christian Fellowship is to establish and advance at colleges and universities witnessing communities of students and faculty who follow Jesus as Savior and Lord: growing in love for God, God’s Word, God’s people of every ethnicity and culture, and God’s purposes in the world." — IVCF, Our Purpose

Leadership: Susan Park, Area Director

Contact: newengland@intervarsity.org

InterVarsity has ministries, groups, or staff covering the following campuses: Babson College, Berklee College of Music (including Boston Conservatory), Boston College, Boston University, Brandeis University, Bunker Hill Community College, Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (MCPHS), New England Conservatory, Northeastern University, Radcliffe College, Tufts University, and the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Some ministries on various campuses are focused on serving specific undergraduate or graduate groups. For example, Harvard Graduate School Christian Fellowship serves Harvard graduate students in the Law School, Business School, and others.

For contacts and information on staff or groups, visit intervarsity.org/chapters.

Cru Boston

“Cru is a caring community passionate about connecting people to Jesus Christ. Our purpose is helping to fulfill the Great Commission in the power of the Holy Spirit by winning people to faith in Jesus Christ, building them in their faith and sending them to win and build others. We help the body of Christ to do evangelism and discipleship in a variety of creative ways. We are committed to the centrality of the Cross, the truth of the Word, the power of the Holy Spirit and the global scope of the Great Commission. … Cru offers spiritual guidance, resources and programs tailored to people from all cultures in every walk of life.” — Cru, What We Do

Website: cruboston.com

Leadership: Sharon Kumar, Cru Team leader in Boston

Staff contacts: cruboston.com/contact

Cru has groups, ministries, or staff covering the following campuses: Babson College, Berklee College of Music (including Boston Conservatory), Boston College, Boston University, Brandeis University, Bunker Hill Community College, Emerson College, Emmanuel College, Harvard University, Lesley University, Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt), Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (MCPHS), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), New England Conservatory of Music, Northeastern University, Roxbury Community College, Simmons University, University of Massachusetts Boston, Wellesley College, and Wentworth Institute of Technology.

Navigators

“The Navigators Christian Fellowship at Boston University is a community of students and friends who want to know God and Jesus Christ and who want to love and encourage each other while walking through life together in Boston.” — The Navigators Christian Fellowship at Boston University

The ministry has weekly small-group Bible studies and large-group meetings.

Navigators is a 90-year-old international, interdenominational Christian ministry known for its emphasis on discipleship and its motto, “to know Christ and to make him known.”

Website: bunavs.org

Craig Parker, City Leader

Rich Brzoska, Campus Director

Chi Alpha

Chi Alpha is a campus ministry that seeks to reconcile students to Christ and build a strong foundation for a lifelong relationship with Him. It is affiliated with the Assemblies of God denomination.

In Boston, there are Chi Alpha Christian Fellowships at Boston College, Boston University, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Website: chialpha.com

Christian Union

Christian Union seeks to “bring spiritual transformation and renewal to campus by seeking the Lord, growing in knowledge and love of His Word.” Staff teach “intellectually rigorous Bible courses, disciple students one-on-one, and coach students to develop as Christian leaders.” — Christian Union

Christian Union ministers at Harvard University and Harvard Law School.

Website: cuglorialaw.org

Leadership

Don Weis, Christian Union Director of Undergraduate Ministry at Harvard

Justin Yim, Christian Union Ministry Director at Harvard Law

Contact: glorialaw@christianunion.org

Coalition for Christian Outreach

Coalition for Christian Outreach is a national student ministry partnering with local churches. Its vision is to see students empowered by the Holy Spirit to live out the public implications of their personal transformation in every sphere of life. They love Jesus intimately, view the world Biblically, live obediently, join in Christ’s restoration of all things, and invite others to do the same.

Locally, the ministry serves students at Boston College and Berklee College of Music and partners with the Church of the Cross.

Leadership: Garrett Rice, Campus Minister, Boston College

International Students Inc. (ISI)

“International Students, Inc. exists to share Christ’s love with international students and to equip them for effective service in cooperation with the local church and others.” — International Students, About Us

Leadership: Steve Hope, ISI Boston City Director

Boston International Student Ministry

“Our mission is to collectively serve international students, scholars, and their families by providing valuable services and activities. … The services we offer consist primarily of friendship partners, holiday host families, seminars, tourism, and ESL classes (conversational and academic). Spiritual activities such as Bible studies and church participation are also offered for those who are interested.” — Boston International Student Ministry, About Us

Website: ismbostonwest.org

Contact: Michael Dean

For more information on international student ministry in Boston, see the Emmanuel Gospel Center’s New England’s Book of Acts, Section 2, pp. 103-113.

Reformed University Fellowship (RUF)

“Reformed University Fellowship - (RUF) is a campus ministry that reaches college students from all backgrounds with the hope of Jesus Christ. College is a time when beliefs are explored, decisions are made, and lives are changed. We invite students into authentic relationships and the study of God’s Word.” — Reformed University Fellowship

Boston University

Website: rufbu.com

Campus minister: Nathan Dicks

Harvard University

Website: ruf.org/ministry/harvard-university

Campus minister: Michael Whitham

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Website: ruf.org/ministry/massachusetts-institute-of-technology

Campus minister: Solomon Kim

Sojourn Collegiate Ministry

Sojourn is a New England campus ministry with a focus on community, justice, and faith. Serving Northeastern University, Boston University, University of Massachusetts, Boston and Tufts University (Bread Coffeehouse).

Website: sojourncollegiate.com

Leadership

Boston Lead: Linsey Field

Executive Director: Tim Hawkins

The Archdiocese of Boston has a Campus Ministry Office with links and information about its many Catholic campus ministries: bostoncatholic.org/chaplaincy-programs/college-campus-ministry.

Athena Grace via Lightstock

Churches with college student ministries or serving college students

Abundant Life Church, Cambridge

A number of college students attend this church led by Pastor Larry Ward. Associate Pastor Kadeem Massiah is experienced in campus ministry.

Website: alccambridge.org

Phone: (617) 864-2826

Bethel AME Church

College Corner is Bethel AME’s college ministry.

Website: bethelame.org/church-school

Facilitators: Sis. Shironda White & Rev. Carrington

Phone: (617) 524-7900

Boston Chinese Evangelical Church (BCEC)

BCEC has a long history of serving college students.

Website: bcec.net

College ministry staff

Ryan So, Director Young Adult & College Ministries, (617) 426-5711, x219

Chris Horte, Director of Student Ministries, Newton Campus, (617) 243-0100 x207

Central Square Church, Cambridge

The conveniently located congregation tends to have many college students attending.

Website: centralsquare.church/youngadults

College ministry staff

Jean Shim, Pastor of Young Adults & Ministries

Phone: 617-420-2232

Email: info@centralsquare.church

Christ the King Church, Cambridge

Christ the King is centrally located between Harvard and MIT at 99 Prospect St. in Cambridge and supports several Reformed University Fellowship groups on campuses.

Website: ctkcambridge.org/college

Phone: (617) 864-5464

Church of the Cross

The campus ministry is a partner with Coalition for Christian Outreach, which is a national student ministry partnering with local churches: ccojubilee.org/about-us.

Website: cotcboston.org/staffandclergy

College ministry staff

Garrett Rice, Director for Collegiate and Young Adult Ministry

City Life Church

City Life Church serves students from many campuses with community groups, monthly city-wide meetings, and retreats.

Website: citylifeboston.org/university

Hyunjo Park and Jamie Lee, University Ministry Interns

Cornerstone Church of Boston

Cornerstone has both young adults and students in its congregation. Its campus ministry contact person is Danny Yoon.

Jubilee Christian Church

Jubilee’s College & Young Adult Ministry is called “Influence.”

Website: jubileeboston.org/influence

Phone: (617) 296-5683

Email: connect@jubileeboston.org

Park Street Church (PSC)

PSC partners with Cru Boston to reach undergraduates and InterVarsity to reach graduate students on campus, but college students involved at Park Street Church also participate in other on-campus ministries.

Ministries

College community: parkstreet.org/ministries/college/

Internationals: parkstreet.org/ministries/internationals

Boston Healthcare Fellowship: healthcarefellowship.org

Staff

Polo Kim, Minister to Internationals

Symphony Church

The Symphony College Congregation meets at 967 Commonwealth Ave. in Boston.

Website: symphonychurch.com/college

Email: admin@symphonychurch.com

Staff

Michael Oh, College Pastor

*For more complete information on churches, see our online Church Directory.

Aimee Whitmire via Lightstock

College Campuses & Christian Ministries Serving Them

Babson College

Cru, IVCF

Berklee College of Music

Cru, IVCF, Coalition for Christian Outreach, Berklee House of Prayer

Boston College

Cru, IVCF, Coalition for Christian Outreach, Chi Alpha, Asian Baptist Student Koinonia (ABSK)

Boston University

Cru, IVCF, Navigators, Reformed University Fellowship, Sojourn Collegiate Ministry, Chi Alpha, Asian Baptist Student Koinonia (ABSK)

Brandeis University

Cru, IVCF, Asian Baptist Student Koinonia (ABSK)

Bunker Hill Community College

Cru, IVCF (Christian Fellowship)

Curry College

IVCF - Crossroads, JAM, Office of Spiritual Life

Emerson College

See nearby Park Street Church, City Life Church, & Cornerstone Church

Center for Spiritual Life: emconnect.emerson.edu/organization/spirituallife

Emmanuel College

Cru, IVCF, Mission and Ministry (including Community Service)

Harvard University

Cru, IVCF, Christian Union Gloria, Southern Baptist Chaplaincy, Foursquare Church Chaplain, Reformed University Fellowship (PCA), Asian Baptist Student Koinonia (ABSK), and other denominational chaplaincies. Radcliffe also has an IVCF group.

Lesley University

Massachusetts College of Art and Design (MassArt)

Cru, IVCF

Massachusetts College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences (MCPHS)

Cru, IVCF

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Cru, IVCF, Reformed University Fellowship, Chi Alpha (Baptist Student Fellowship), Asian Baptist Student Koinonia, Octet Collaborative-Christian Study Center, Cambridge Roundtable on Science and Religion (for faculty, contact: dyamash@mit.edu)

New England Conservatory of Music

Cru, IVCF (NEC Christian Fellowship)

Northeastern University

Agape Christian Fellowship (CRU), InterVarsity Christian Fellowship, Asian Baptist Graduate Student Koinonia, Chinese Christian Fellowship, Open Table (Lutheran-Episcopal Campus Ministry), Sojourn Collegiate Ministry, Youth Empowerment Ministry, and YWAM Friends (International Students)

Roxbury Community College

Cru

Simmons College

Cru

Suffolk University

Youth Empowerment Ministry

See nearby Park Street Church, City Life Church, and Cornerstone Church

Tufts University

C. Stacey Woods Programming Board (Partnering with IVCF), University Chaplaincy, Sojourn Collegiate Ministry (Bread Coffee House)

University of Massachusetts, Boston

Cru, IVCF, Sojourn Collegiate Ministry, UMB Christians On Campus, First Love UMass, and Life On Campus

Wellesley College

Cru, IVCF, Asian Baptist Student Koinonia (ABSK), Wellesley Symphony Church group, Awaken the Dawn (Christian Acapella Group), Wellesley CityLife Church group

Wentworth Institute of Technology

Cru, Alpha Omega

To find further information about specific campuses and groups, you can typically use a search with the following pattern: “name of school” and “student organizations” (category: religious & spiritual).

Greater Boston Chinese Church Listing

A listing of Chinese churches in Greater Boston, derived from many online sources and from the ongoing research of EGC. This serves as a resource page to a 2016 article on the current status of Chinese churches in this region. There is also a link to a corresponding map.

About. This listing shows churches in Greater Boston that hold services in Mandarin or Cantonese, or otherwise strongly identify with the region's Chinese population. Last update: March 2017.

Map. For an interactive map of Chinese churches in Greater Boston, click here.

Study. Read a 2016 analysis of the current status of the Chinese church community in Greater Boston, posted here.

Church Directory. You may also be interested in our online Boston Church Directory, with listings for Christian churches in Boston, Brookline, and Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Updates. Help us keep these data current by letting us know about corrections and updates. Write Rudy Mitchell by clicking the Contact EGC button on this page, or call (617) 262-4567 during regular business hours.

| Church/Address | Pastor/Phone | Website/Languages Year Founded |

|---|---|---|

| Boston Chinese Church of Saving Grace 115 Broadway Boston, MA 02116-5415 |

Pastor Kai P. Chan (617) 451-1981 |

http://www.bccsg.org Mandarin, Cantonese, English 1985 |

| Boston Chinese Evangelical Church – Boston Campus 249 Harrison Ave. Boston, MA 02111-1852 |

Rev. Steven Chin (617) 426-5711 |

http://www.bcec.net/ Cantonese, English, Mandarin 1961 |

| Boston Chinese Evangelical Church – Newton Campus 218 Walnut Street Newtonville, MA 02460 |

(617) 243-0100 | Cantonese, Mandarin, English 2003 |

| Boston MetroWest Bible Church 511 Newtown Road Littleton, MA 01460 |

Acting Pastor Elder Mingche Li (978) 486-4598 |

http://www.bmwbc.org Mandarin, English 2010 |

| Boston Taiwanese Christian Church 210 Herrick Road Newton Centre, MA 02459 |

Rev. Michael Johnson (781) 710-8039 |

https://sites.google.com/site/bostontcc Taiwanese, English 1969 |

| Chinese Alliance Church of Boston 74 Pleasant Street Arlington, MA 02476 |

Dr. Peter K. Ho (781) 646-4071 |

Cantonese 1982 |

| Chinese Baptist Church of Greater Boston 38 Weston Avenue Quincy, MA 02170 |

Rev. XiangDong Deng (617) 479-3531 |

http://www.cbcogb.org/ Mandarin, Cantonese, English 1982 |

| Chinese Bible Church of Greater Boston – Lexington Campus 149 Old Spring St. Lexington, MA 02421 |

Pastor Caleb K.D. Chang (781) 863-1755 |

https://www.cbcgb.org/ Mandarin, English 1969 |

| Chinese Bible Church of Greater Boston – City Outreach Ministry 874 Beacon Street Boston, MA 02215 |

Rev. Dr. JuTa Pan (617) 299-1266 |

https://www.cbcgb.org/com Mandarin 2010 |

| Chinese Bible Church of Greater Boston – Cross Bridge Congregation 149 Old Spring St. Lexington, MA 02421 |

Pastor David Eng (781) 863-1755 |

http://www.crossbridge.life/ English 2016 |

| Chinese Bible Church of Greater Boston – Metro South 2 South Main Street Sharon, MA 02067 |

Rev. Dr. Wei Jiang (781) 519-9672 |

http://ccbms.org/ Mandarin, English 2011 |

| Chinese Bible Church of Greater Lowell 197 Littleton Rd #B Chelmsford, MA 01824 |

Pastor Peter Wu (978) 256-3889 |

http://cbcgl.org/ Mandarin, Cantonese, English 1989 |

| Chinese Christian Church of Grace 50 Eastern Ave. Malden, MA 02148 |

Rev. He Rongyao (781) 322-9977 |

http://maldenchurch.org Mandarin, Cantonese 1993 |

| Chinese Christian Church of New England 1835 Beacon St. Brookline, MA 02445-4206 |

(617) 232-8652 | http://www.cccne.org/ Mandarin, English 1946 |

| Chinese Gospel Church of Massachusetts 60 Turnpike Road Southborough, MA 01772 |

Pastor Sze Ho Lui (508) 229-2299 |

http://www.cgcm.org/ Mandarin, Cantonese, English, Taiwanese 1982 |

| Christian Gospel Church in Worcester 43 Belmont Street Worcester, MA 01605 |

Rev. Daniel Shih (508) 890-8880 |

http://www.worcestercgc.org Mandarin, English 1999 |

| City Life Church – Chinese Congregation 200 Stuart St. Boston, MA 02116 |

(617) 482-1800 | http://www.citylifecn.org/ Mandarin 2002 |

| Emeth Chapel 29 Montvale Ave. Woburn, MA 01801 |

Rev. Dr. Tsu-Kung Chuang (978) 256-0887 |

https://emethchapel.org Mandarin, English 2002 |

| Emmanuel Anglican Church (Chinese) 561 Main St. Melrose, MA 02176 |

(718) 606-0688 | http://www.emmanuelanglican.org/ Cantonese 2014 |

| Episcopal Chinese Boston Ministry 138 Tremont St. Boston, MA 02111-1318 |

Rev. Canon Connie Ng Lam (617) 482-5800 ext. 202 |

http://www.stpaulboston.org/ Mandarin 1981 |

| Good Neighbor Chinese Lutheran Church 308 West Squantum St. Quincy, MA 02171 |

Rev. Ryan Lun (617) 653-3693 |

https://gnclc.org Cantonese, Mandarin 2013 |

| Greater Boston Chinese Alliance Church 239 N. Beacon Street Brighton, MA 02135 |

Rev. Frank Chan (617) 254-4039 |

https://gbcac.net/ Cantonese, English 1986 |

| Greater Boston Christian Mandarin Church 65 Newbury Ave. North Quincy, MA 02171 |

Rev. Paul Lin (720) 840-0138 |

http://www.gbcmc.net/ Mandarin, English 2012 |

| Lincoln Park Baptist Church 1450 Washington Street West Newton, MA 02465 |

Rev. Jie Jiao (857) 231-6904 |

http://www.lpb-church.org/ 2007 (1865, English congregation) |

| Quincy Chinese Church of the Nazarene 37 East Elm Ave Quincy, MA 02170 |

Rev. Sze Ho (Christopher) Lui (617) 471-5899 |

2003 |

| River of Life Christian Church in Boston 45 Nagog Park Acton, MA 01720 |

Rev. Jeff Shu (978) 263-6377 |

http://www.rolccib.org 2006 |

| Saint James the Greater 125 Harrison Ave. Boston, MA 02111 |

Rev. Peter H. Shen (617) 542-8498 |

Cantonese, English, Mandarin 1967 |

| Taiwan Presbyterian Church of Greater Boston 14 Collins Road Waban, MA 02468 |

Rev. David Chin Fang Chen (617) 445-2116 |

http://www.tpcgb.org Taiwanese 1991 |

| Wollaston Lutheran Church - Chinese Congregation 550 Hancock Street Quincy, MA 02170 |

Rev. Richard Man Chan Law (617) 773-5482 |

http://www.wlchurch.org/cm/ Cantonese, English, Mandarin (translation) 1989 |

Perspectives on Boston Church Statistics: Is Greater Boston Really Only 2% Evangelical?

A frank look at the sources, accuracy, limitations, and weaknesses of some commonly used church statistics in Boston. As convenient and convincing as statistics are, they can be misunderstood, misapplied, and generate misinformation.

Resources for the urban pastor and community leader published by Emmanuel Gospel Center, Boston

Emmanuel Research Review reprint

Issue No. 88 — April 2013

Introduced by Brian Corcoran, Managing Editor, Emmanuel Research Review

What are the sources, accuracy, limitations, and weaknesses of some commonly used church statistics, especially with regard to their application in Boston? Wanting to encourage a more appropriate use of church statistics generally and in Boston, Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher at EGC, considers some of the more popular sources we encounter on the internet or in the news media, such as:

The U. S. Religious Census and the Association of Religious Data Archives

The Barna Research Group, and

Gallup Polls on Religion.

Rudy offers some quick and practical advice for those who are tempted to grab-and-go with the numbers, as if they were “gospel” to their next sermon, strategic planning meeting, church planting support fundraising website, or denominational report. As convenient and convincing as statistics are, beware! They also can be easily misunderstood, misapplied, and generate misinformation.

True or false?

“...only 2.1% of the people living in greater Boston attend evangelical churches.”

“Tragically, only 2.5% of the 5.8 million people in greater Boston attend an evangelical church.”

“Boston is...97.5% non-evangelical.”

“There are fewer than 12 Biblical, Gospel Centered, Soul-Winning Churches” among the “7.6 million people” in Greater Boston.

The twitter-speed circulation of misinformation about Greater Boston being only 2% evangelical contributes to an inaccurate portrayal of what God has been doing in Greater Boston for decades by failing to recognize the ministry of many existing evangelical churches. Furthermore, it misdirects the development of new ministries and leaders emerging and arriving in Boston each month.

The good news is that the local church research conducted by the Emmanuel Gospel Center in Boston over the last 40 years has identified a larger, more vital, and more ethnically diverse Church than suggested by recent and broader church research projects. With the benefit of a comprehensive database and directory of the churches in Boston, developed over decades, EGC has the opportunity to compare and contrast our street-by-street Boston results with broader, less dense, bird’s-eye-view national research. With all this info in hand, we can illustrate how Boston’s evangelical churches have been significantly underreported in national surveys and suggest that they might also be underreported in some other major U.S. cities. Go ye therefore and research your city.

Furthermore, given the longevity of our research, we have been able to identify what we call Boston’s “Quiet Revival,” which is characterized by growth in the number of churches and church attendees, increased collaborative ministry, and multiple interrelated prayer movements in Boston since 1965. Currently there are approximately 700 Christian churches in the three cities of Boston, Brookline and Cambridge in the heart of Metro Boston, and these churches include folks from many tongues, tribes, and nations.

God is and has been doing more in Boston than most national survey techniques can identify.

Perspectives on Boston Church Statistics: Is Greater Boston Really Only 2% Evangelical?

by Rudy Mitchell, Senior Researcher, Emmanuel Gospel Center

Infographics by Jonathan Parker

What about the U. S. Religious Census and the Association of Religious Data Archives (ARDA)?

The 2010 U.S. Religious Census was collected by the Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies (ASARB) and also presented by the Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). The 2010 U.S. Religious Census provides data by county and by metropolitan area. The method used by this census is basically to compile the numbers of churches and adherents, denomination by denomination. The Boston city data is a part of Suffolk County, which also includes the cities of Chelsea, Winthrop and Revere.

Through our research at Emmanuel Gospel Center, we have identified over 500 Christian churches within the city limits of Boston. The other three cities in Suffolk County have at least an additional 54 churches. Therefore, through first-hand research, we have counted at least 554 Christian churches in Suffolk County. The U.S. Religious Census counted only 377 Christian churches.1 Thus their count misses at least 177 churches. Because many new churches have been planted since our last count in 2010, we estimate that the U.S. Religious Census may have missed as many as 200 to 240 churches. In urban areas, the U.S. Religious Census / ARDA statistics are especially inaccurate because few African American, Hispanic, and other immigrant churches are counted, since many do not appear in the denomination lists used by the census. Other independent churches, some of which are very large, are often missed as well.

While the U.S. Religious Census perhaps needed to make some simple classifications of churches for the national compilations, these classifications are oversimplified and often misleading, especially at the local level. In urban areas there are many evangelical churches within denominations classified as “Mainline.” For example, in the city of Boston, the vast majority of American Baptist Churches (classified as Mainline) are evangelical. Other so-called “Mainline” denominations have some evangelical churches in Boston as well. Therefore, if one compiles the number of evangelical churches and adherents only from the list of churches classified as “Evangelical” by the U.S. Religious Census, one will end up with serious errors.

In addition, while the term “evangelical” is not typically used by African American churches, a majority of those churches would be considered “evangelical” in light of their beliefs and practices. This is also true of most Protestant Spanish-speaking and Haitian churches. In Suffolk County our research has identified at least 120 Spanish-speaking churches, and the vast majority of these are evangelical. Therefore, counts of evangelical churches and adherents must include these and additional immigrant evangelical church groups, if they are to be accurate.

Likewise, in urban areas like the city of Boston, most Black Protestant churches are missed by the U.S. Religious Census. The commentary notes that this is the case. Although the census attempted to include the eight largest historically African American denominations, it fell far short of gathering accurate numbers for even these denominations. “Based on the reported membership sizes included in the address lists, less than 50% of any group’s churches or members were able to be identified… For the African Methodist Episcopal Church, they found approximately the correct number of congregations, though the membership figures are only about one-third of their official reports. For other groups, the church counts range from 11% to 50% of reported numbers, and membership figures are from 7% to 28% of the reported amounts.”2 In the case of Boston, one can see just how far off these numbers are. The Boston Church Directory research identifies 144 primarily African American churches, 19 Caribbean/West Indian churches, 9 African churches, and 34 Haitian churches in the city of Boston for a total of 206 Black churches. In contrast, the U.S. Religious Census identifies only 23 Black Protestant churches in all of Suffolk County. Thus the Census identifies (as Black Protestant) less than 11% of the Black churches that exist in the city. Given the size and importance of Black churches in urban areas, the U.S. Religious Census is completely inadequate in assessing religious participation in cities. Many of these churches belong to small denominations or are independent. While some Black churches are counted as part of evangelical and mainline denominations, they are not identified as Black churches.

At a time when hundreds of new evangelical churches have been planted in Boston and the greater Boston area, a number of church planters and media sources continue to lament the “cold, dark, sad and tragic” state of the Boston spiritual climate. While there is still a need for increased growth and vitality of many current churches, and a need for new church plants, these reports often give a one-sided and overly pessimistic view of the state of the Christian church in Boston. It is common to hear that only 2.1 or 2.5% of greater Boston residents are evangelicals. This number is passed on from source to source without question, often morphing and attaching itself to various subgroups of the population. This percentage underestimates and diminishes the work of God which is going on in greater Boston.

One can easily glean a sad harvest of bad news about Boston on the internet. For example, a web-posted Boston church planting prospectus says, “What most people do not consider is the spiritual brokenness that fractures the city. They fail to realize that the spiritual climate is incalculably colder than the lowest lows of a Boston winter…most remain blind to the spiritual darkness that pervades the city. Tragically, only 2.5% of the 5.8 million people in greater Boston attend an evangelical church. Not surprisingly, there are very few healthy evangelical churches…” Another church planter said, “According to one very thorough study, only 2.1% of the people living in greater Boston attend evangelical churches.” One church planter recalled God’s call, “God said, “I’m going to give you somewhere.’ I had no idea he was going to give me one of the hardest cities in the United States to go plant a church in…Boston is very intimidating. It’s 97.5% non-evangelical. For those non-math people, that’s 2.5 percent evangelical Christian. I didn’t even know there was a city like that before I started studying it.” While it may be more difficult to plant a new church in urban Boston than in suburban Texas or North Carolina, hundreds of successful churches have been planted in greater Boston in the last few decades.

In the city of Boston and surrounding towns, God has raised up new churches among many different groups of people. For example, in the city of Boston alone, more than 100 Spanish language churches have been planted. Many of these are not counted in typical “thorough” studies because they are either independent or do not belong to the denominations counted in these studies. In greater Boston there are even more Spanish speaking churches than in the city itself. Likewise the research often referenced does not count most of the Brazilian churches in greater Boston. The majority of the 420 Brazilian churches in eastern New England are located in Greater Boston. As many as 180 of these churches are nondenominational or directly affiliated with their denominations in Brazil, and therefore not counted in the ARDA data.3 Scores of African American, Haitian, African, Korean, Indonesian, and Chinese churches have also been planted in this area as well. Most, if not all of these immigrant churches would be considered evangelical. While some of these are small, quite a number of the churches have hundreds of active participants. Although one church planter claimed there was only one successful Anglo church plant, a little more research would have revealed that God has been growing many new and successful churches among this group, especially reaching Boston’s young adult population.

The source for some of the above statistics on greater Boston is based on the Association of Religion Data Archives information from 2000 which was also analyzed by the Church Planting Center at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.4 The Center’s report and PowerPoint presentation state that greater Boston is 2.5% evangelical.5 Since the ARDA data fails to include most of the Black Protestant, Hispanic, Haitian, Brazilian, and Asian churches under its evangelical category, it clearly underestimates the evangelical percentage. Even the slightly improved 2010 ARDA data only identifies 7,439 Black Protestants in Greater Boston.6 Just one black church (Jubilee Christian Church) of the city of Boston’s more than 200 black churches has about that number of members. In Greater Boston, there are many more black churches not counted in this study. If the city of Boston has about 100 largely uncounted evangelical Spanish-speaking churches, then Greater Boston (which includes Lawrence, Mass.) has at least double that number. This study also does not account for the many evangelical churches which in urban areas are affiliated with denominations classified by ARDA as “Mainline.” For example, more than 60 American Baptist churches in Greater Boston could be classified as evangelical rather than mainline. Numbers and percentages based on the ARDA data, therefore, fail to identify hundreds of evangelical churches in Greater Boston, and some of these are among the area’s largest churches.

What about the Barna Research Group?

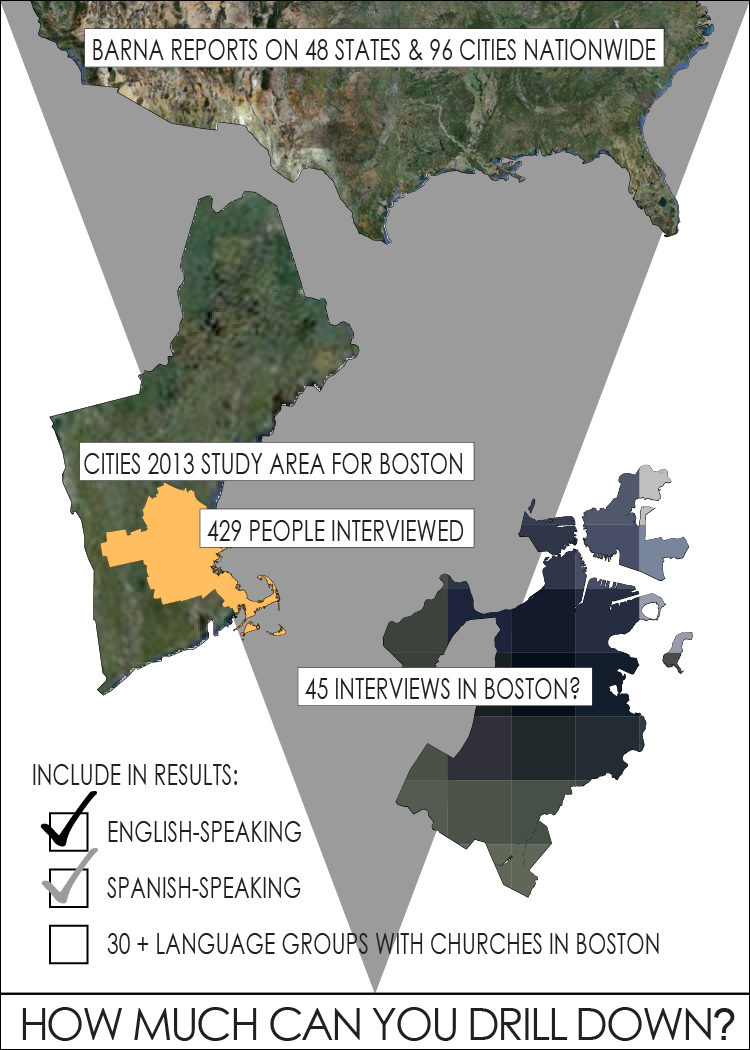

The Barna Research Group has produced many reports on the beliefs and practices of Americans using phone surveys. By drawing on 42,000 interviews completed over the last five to ten years, they have compiled statistics which they have sliced up into 96 cities ("urban media markets”). The most recent of these Barna Reports are called Cities 2013. Barna also has produced parallel reports on 48 states.

The Cities 2013 report for the Boston area might give the impression to many people that it gives data primarily on the city of Boston or the city and its immediate suburbs. It is important to realize that this report covers an area extending from Nantucket to Laconia, New Hampshire, and eastern Vermont, as well as Worcester County, Massachusetts. The adult population of this media market area (DMA) in 2010 was 4,946,945 while the city of Boston’s adult population was 513,884 or only 10.4% of the total area.7 The total population of Barna’s “Boston” area was 6,322,433 compared to the total Boston city population of 617,594 (9.8% of the area). When using statistics from the Barna Cities 2013 report, one must keep in mind that the city of Boston is only a small part (~10%) of the area covered.

The Boston Cities 2013 Report is based on 429 interviews according to the Barna Research Group. Since the city of Boston represents 10.4% of the area’s adult population, one can estimate that about 45 interviews were done in Boston. Given the diversity of languages, racial groups, and nationalities in the city with its population of over a half-million adults, it is hard to imagine that this sample was large enough and representative enough to give a true picture of religious faith and practice in Boston. In addition, “while some interviews were conducted in Spanish, most were conducted in English. No interviewing was done in languages other than Spanish and English.”8 In fact, the Barna website says, “the vast majority of the interviews were completed in English.”9 Since the city of Boston has over 100,000 (17.5%) Hispanics10 with more than 100 churches, it is quite likely this group is underrepresented. This is just one of over 30 language groups which have churches in Boston. In the larger Barna study area (Boston DMA), there are 522,867 Hispanics and 344,157 Asians.11 The area also includes a very large Brazilian population with over 400 Brazilian churches and the fourth largest population of Haitian Americans with dozens of thriving Haitian churches. Because these language groups were significantly less likely to be included in the interviews, and because many of these groups are among the most active in Christian faith and practice, the Boston area report underestimates Christian beliefs and involvement in the area and especially if one equates its conclusions with the city of Boston.

Table of total populations of the City of Boston and the DMA media market area. (The Boston DMA area is the one used by the Barna Research group.)

What about the Gallup Polls on religion?

The Gallup organization interviews large numbers of adults every year on a variety of topics including religion. Recent reports have not only examined national trends, but have also analyzed how religious the various states and metropolitan areas are. During 2012, Gallup completed more than 348,000 telephone interviews with American adults aged 18 years and over.12 The Gallup organization uses what it calls the Gallup Religiousness Index when it states that one state or city is more religious than another. Specifically it is comparing the percentage of adults in the various states or cities who are classified as “very religious.” Two questions are used in the Gallup Religiousness Index:

(2) “How often do you attend church, synagogue or mosque? – at least once a week, almost every week, about once a month, seldom, never, don’t know, refused.”13

For someone to be classified as “very religious,” he or she would need to answer, “Yes, religion is an important part of my daily life,” and “I attend church, synagogue, or mosque at least once a week or almost every week.”

Nationally, 40% of American adults were found to be “very religious” on the basis of this standard. Significantly more Protestants (51%) were “very religious” than Catholics (43%).14 Religiousness generally increases with age, and so young adults are less religious than seniors.

The Gallup surveys have found that the New England states, including Massachusetts, have lower percentages of adults who are “very religious.” In fact, (1) Vermont (19%), (2) New Hampshire (23%), (3) Maine (24%), (4) Massachusetts (27%), and (5) Rhode Island (29%) are the five least religious states according to this measure.15 Several New England metropolitan areas also ranked low on the religiousness scale (Burlington, VT; Manchester-Nashua, NH; Portland, Maine). The Boston-Cambridge-Quincy metropolitan area ranked eighth least religious, with 25% of its metro area adults classified as “very religious.”16 Although many new churches have started in Boston and there is significant spiritual vitality in the city, two factors probably contribute to the low ranking. Boston has the largest percentage of young adults aged 20 to 34 years old of any major city in the country. This age group has lower percentages of “very religious” people than the older age groups. Also, Boston has a high percentage of Catholics (46.4%), and Catholics have a significantly lower percentage of “very religious” adherents.17 This factor also plays a role in the Massachusetts state ranking, since Massachusetts is now “the most heavily Catholic state in the union” (44.9%).18 One must keep in mind that the Gallup Religiousness Index is just one way of measuring how religious a person is, and it is based on self-reporting. The question about the importance of religion in one’s daily life can have many different meanings to different people. Other research has shown that the frequency of church attendance “does not predict or drive spiritual growth” for all groups of people.19

Some Quick Advice for Boston Church Statistic Users

From these examples, you can see that it is important to evaluate critically the religious statistics you read in the media. In some cases these statistics may be incomplete, inaccurate, or have large margins of error. In looking at the data for a city, you also need to understand the geographic area the report is studying. This could range from the named city’s official city limits, to its county, metropolitan statistical area, or even to a media area covering several surrounding states. In reading religious statistics and comparisons, you also need to carefully understand definitions and categories that the research uses. A study may categorize and count Black churches or Evangelical churches in ways that fail to count many of those churches. When a survey says one state is more religious than another, you need to understand how the study defines “religious.” Using religious research statistics without careful evaluation and study can lead to misinterpretation and spreading misinformation.

_______________

1 To accurately compare numbers, we compare only Christian churches from both our count and the U.S. Religious Census (which also included other religious groups such as Buddhists, etc.).

2 “Appendix C / African American Church Bodies,” 2010 U. S. Religion Census: Religious Congregations & Membership Study, 675, www.USReligionCensus.org (accessed 28 March 2013).

3 Cairo Marques and Josimar Salum, “The Church among Brazilians in New England,” in New England’s Book of Acts, edited by Rudy Mitchell and Brian Corcoran (Boston: Emmanuel Gospel Center, 2007), II:15. See link here.

4 J. D. Payne, Renee Emerson, and Matthew Pierce, “From 35,000 to 15,000 Feet: Evangelicals in the United States and Canada,” Church Planting Center, Southern Baptist Theological Center, 2010.

5 Ibid.

6 Association of Religion Data Archives, “Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA, NH Metropolitan Statistical Area: Religious Traditions 2010,” www.thearda.com (accessed 5 May 2013).

7 U.S. Census 2010, Summary File 1, Table DP1 (Population 18 and over). The Barna interviews were only with adults.

8 Pam Jacob, “Barna Research Group,” Email. 2 April 2013.

9 Barna Research Group, “Survey Methodology: The Research Behind Cities,” Barna: Cities. Barna Cities & States Reports (accessed 8 April 2013).

10 U.S. Census 2010, Summary File 1, Table DP1.

11 U. S. Census 2010, Summary File 1, Table DP1.

12Frank Newport, “Mississippi Maintains Hold as Most Religious U.S. State,” Gallup, 13 Feb. 2013 www.gallup.com (accessed 24 April 2013).

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Catholic Hierarchy website, Boston Archdiocese, 2006, www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/dbost (accessed 24 April 2013).

18 “Massachusetts Now Most Catholic State,” Pilot Catholic News, 11 May 2012, www.PilotCatholicNews.com (accessed 24 April 2012)

19 Greg L. Hawkins and Cally Parkinson, Move: What 1,000 Churches Reveal About Spiritual Growth (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2011), 18-19.

Keywords

- #ChurchToo

- 365 Campaign

- ARC Highlights

- ARC Services

- AbNet

- Abolition Network

- Action Guides

- Administration

- Adoption

- Aggressive Procedures

- Andrew Tsou

- Annual Report

- Anti-Gun

- Anti-racism education

- Applied Research

- Applied Research and Consulting

- Ayn DuVoisin

- Balance

- Battered Women

- Berlin

- Bianca Duemling

- Bias

- Biblical Leadership

- Biblical leadership

- Black Church

- Black Church Vitality Project

- Book Recommendations

- Book Reviews

- Book reviews

- Books

- Boston

- Boston 2030

- Boston Church Directory

- Boston Churches

- Boston Education Collaborative

- Boston General

- Boston Globe

- Boston History

- Boston Islamic Center

- Boston Neighborhoods

- Boston Public Schools

- Boston-Berlin

- Brainstorming

- Brazil

- Brazilian

- COVID-19

- CUME

- Cambodian

- Cambodian Church

- Cambridge

![Ethiopian Churches in Greater Boston [map]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57ff1c7ae58c62d6f84ba841/1506113852983-TSLLC1FENTJJGZYIO7MM/orthodox+cross+church.jpeg)